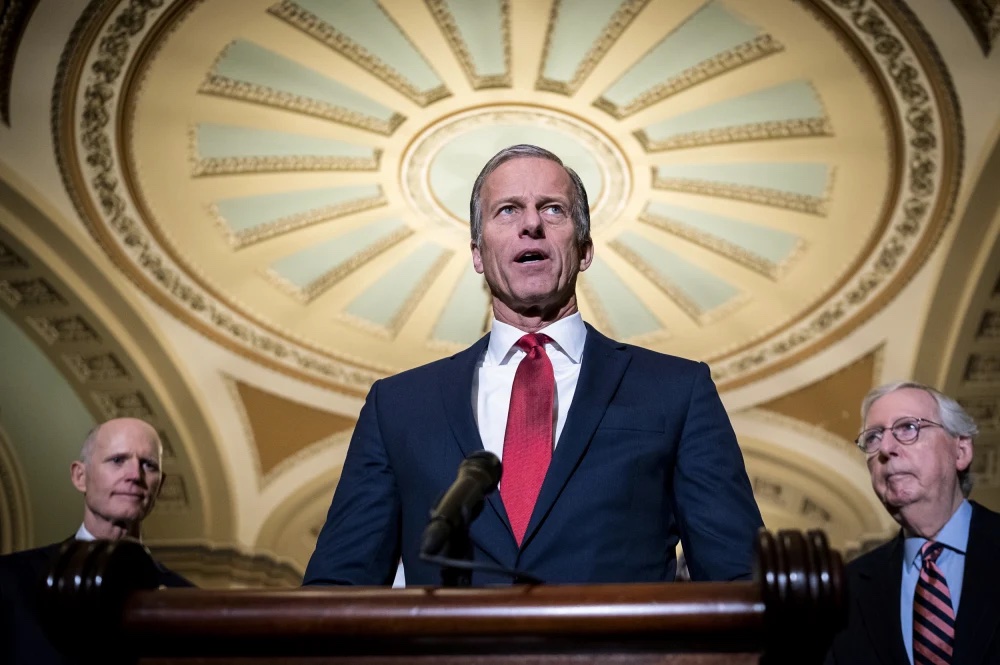

Can John Thune Fix the Senate?

Five-day work weeks. Bringing more bills to the floor. More debate with plenty of opportunity for members to offer amendments?

Is John Thune channeling the “Fixing Congress” agenda?

The Senate’s new Republican leader is certainly sending signals that he intends to restore the upper chamber as a functioning and deliberative legislative body. The tentative schedule he released will have the Senate in session 180 days this year, 43 days more than the Republican-controlled House. That’s what happens when you work five days a week rather than the leisurely three that has become the norm under both Republican and Democratic House. To deal with the crush of nominations to fill the new administration, there will even be a nine week stretch without one of those week-long “state work periods.”

In comments last month, South Dakota’s Thune bemoaned the pile-up “unfinished business” that the previous Democratic majority had left behind, including the normally bipartisan farm and defense authorization bills and 11 of the 12 annual appropriations bills, most of which had been reported by committee months earlier.

“The one thing I can tell you about next year is it is going to be different,” he vowed. “The way the Senate operates today is not the way it’s going to be operating in the future. We aim to fix that, and it’s time – high time—that we start getting the American people’s work done.”

A few weeks later, in his first remarks as the Senate’s new leader, Thune set out his vision of “restoring the Senate as a place of discussion and deliberation.” That vision includes preserving the Senate filibuster that, in effect, requires 60 votes to pass most legislation. And it includes “empowering committees, restoring regular order and engaging in extended debate on the Senate floor, where all members should have a chance to make their voices – and the voices of their constituents – heard.”

The irony, of course, is that Thune got to the Senate 20 years ago by narrowly defeating then Democratic Majority Leader Tom Daschle, arguably the last majority leader committed to “regular order.” Since then, both Republican and Democratic leaders have gradually consolidated power in the leadership offices while avoiding taking up issues on the floor that might jeopardize the unity of their caucuses or alienate key funders and interest groups.

During its remarkably unproductive 2024 session, for example, the Senate was in session for fewer than 800 hours, the lowest since 1990, according to data kept by C-SPAN. And of those 800 hours, fewer than 20 percent of were given over to actual debate on legislation, nominations, or treaties. The rest was taken up by procedural rigamarole, roll calls, and endless quorum calls meant to kill time and obscure the fact that nothing was really going on.

Thune has told colleagues he does not want to be a top-down Senate leader in the mold of Mitch McConnell, Chuck Schumer, or Harry Reid. He wants to return power and initiative to members and sees “extended debate” as a mechanism for producing the kind of bipartisan compromises that will allow a closely divided Senate to legislate again.

At the same time, Thune has also shown a willingness to defend the power, prerogatives, and independence of the Senate in the face of an incoming president who expects a Republican Congress to bend to his will. He quickly shot down the idea of adjourning the Senate this month to give Trump the opportunity to fill his cabinet and other top positions with recess appointments. And in recent days, he made clear he would not go along with the House demand to put the entire Trump agenda into “one big, beautiful bill” to be rammed through both chambers as part of a “budget reconciliation” gambit.

Thune, of course, is under enormous pressure to do whatever is necessary to confirm all of Trump’s cabinet nominees and pass his agenda without making concessions to Democrats or even moderates in his own caucus. His challenge will be to convince Trump – and through Trump, the party’s hardliners – to accept three quarters of a loaf and declare it a victory. He knows that task will be made easier if senators are allowed to have more involvement in, and ownership of, the legislative process.

Democratic leaders face a similar dilemma. Their natural instincts will be to get into a defensive partisan crouch and wage all out resistance to the “radical MAGA agenda, just as Republicans did in response to the Democratic “trifectas” at the outset of the first Obama and Biden terms. The problem with that strategy, however, is that it will give Republican “moderates” like Susan Collins of Maine, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, Todd Young of Indiana, Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, and freshman John Curtis of Utah no other choice but to go along with Trump and the rest of the Republican caucus.

A better Democratic strategy would be to vow all-out resistance while giving moderate Democrats the political headroom to try to hammer out reasonable compromises with their Republican counterparts. If nothing else, putting such compromises on the table will trigger bitter fights within the Republican tent—not only between the hardliners and the moderates in the Senate but between the House and Senate and the White House and Congress. If such compromises win the day, the result would be better policy that would take some of the political sting from the Republican victory in the 2024 election. And if they fail – the more likely outcome, certainly—Congress will quickly settle back into the same unproductive gridlock that will allow Democrats can blame on the Republican President and the Republican-controlled Congress in the 2026 and 2028 elections.

Certainly, this will be a fascinating next six months on Capitol Hill. Contrary to what you often hear, hyper-partisanship and legislative gridlock are not the inevitable outcomes forced on a reluctant Congress by a polarized electorate. They are a choice—a choice made by 535 politicians who must decide whether they want to be leaders or followers, serious legislators or partisan warriors.

Majority Leader John Thune has come out of the gate offering himself up as a leader and a legislator willing to defend the independence and prerogatives of the Senate and imagine a different and better way of conducting its business. How many others will have the courage and the imagination to do the same?

Steven Pearlstein is a Senior Fellow at Penn Washington. He is also the Robinson Professor of Public Affairs at George Mason University and a former Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for the Washington Post. The views expressed here are his own.