Learning to Speak Legalese in Chinese

By: Angela Shen, Huntsman ’24

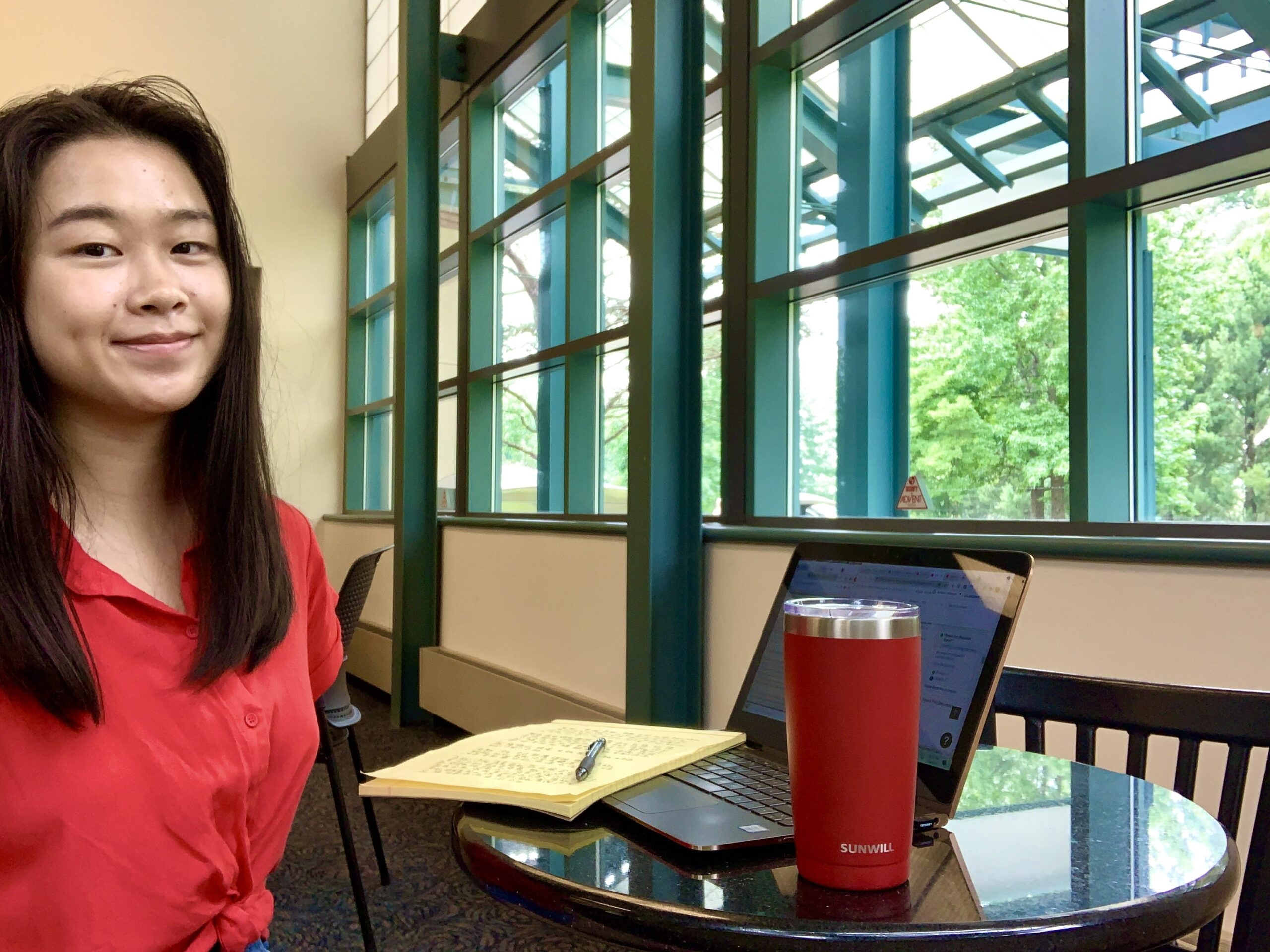

Angela seated by the windows at her local public library, where she completes her work for Grandall Law Firm.

Grandall Law Firm – Beijing, China

“Do you speak Chinese?” One of the first questions out of my interviewer’s mouth as I looked dutifully at his image on my phone screen, still mentally rehearsing the interview answers I had prepared ahead of time.

I had expected this question about my language proficiency, and I quickly responded in the affirmative. What I did not expect was how quickly my interviewer and soon-to-be supervisor switched from English to fluid Mandarin, describing in-depth the legal projects I would eventually be assigned. Was I familiar with foreign trade policy? Could I read through a prospectus for a Chinese company planning to launch an initial public offering in the United States?

I had never used my Mandarin language skills in a professional setting before, and I was excited about the challenge. Pen and notebook in hand, I desperately transcribed as much of the conversation as possible in a written jumble of Chinese and English. I resolved myself to look up and learn every new phrase of Mandarin legalese or business-speak that I would be exposed to by my supervisors and coworkers at Grandall Law Firm (国浩律师事务所), where I am now officially interning.

My newly expanded Mandarin vocabulary helps me use my internship as an opportunity to hone my ability to create real-world impact through law and public policy. Over hours of work at home or in my local library, I have studied the fundamentals of American intellectual property law to share with my supervisors; I have developed my skill at structuring and recording legal research; I have learned the rules governing the behavior of internet service providers like Amazon.

Throughout my research, I am fascinated by the subtle and complex ways that national and international laws influence every aspect of daily life, regardless of where a person lives. Although the words used to describe each idea might be different—“跨境电商” rather than “international e-commerce,” or “知识产权” rather than “intellectual property rights”—these concepts, often intimidating at first, play a role in every American (or Chinese) citizen’s absent-minded scrolling through Instagram (or WeChat) and online shopping binges on Amazon (or Alibaba).

When I originally applied to GRIP: Law and International Affairs in Beijing, I hoped for an immersive professional and living experience through which I could build upon my Chinese linguistic and cultural proficiency to understand the complexities of China’s economic and political context. Although my dreams of wandering the streets of Beijing have been replaced by the cold reality of my laptop screen and a twelve-hour time difference, I have still found opportunities to learn more about China’s language and culture and investigate how policies and laws function, not only in China, but around the world.

The Global Research and Internship Program (GRIP) provides outstanding undergraduate and graduate students the opportunity to intern or conduct research abroad for 8 to 12 weeks over the summer. Participants gain career-enhancing experience and global exposure that is essential in a global workforce.