Visiting the Warm Heart of Africa

PGS: Global Aging – Challenges and Opportunities

Sophia, one of the Penn Global Seminar Correspondents, shares her experience abroad during the Spring 2025 semester. Follow along with the group of correspondents on our blog and look out for their images on the @pennabroad Instagram feed.

Bus rides

The first drive from the airport into Blantyre can only be described as lush. We scramble to open all the windows on the bus until a warm breeze fans against our cheeks like an exhale. For the next thirty minutes, everyone is in a trance – no phones, no earbuds, just rows of students silently craning their necks toward the windows, trying to drink in every inch of a world that was utterly new.

The sun is buttery and the fields are marzipan green and the road stains wheels the color of copper. We see women balancing wide jugs on their heads with grace. We pass shacks with pleated iron roofs and brightly painted signs announcing local shops. Out of nowhere, a BreadTalk pops up, which snaps me straight back to my grandmother’s local mall in Shenzhen.

Over the course of the week, our bus rides became a kind of quiet solace. They were brief windows of stillness as the rest of the trip moved in fast-forward. Looking outside, our rides felt like hazy scenes in a traveling play. Sometimes we drove through the countryside, with maize fields stretching into the horizon. The rolling hills surprised me – I hadn’t realized Malawi was so mountainous, or so green. Our guide told us that the rows upon rows of maize we saw were all planted by hand. Other times, we rolled through bustling marketplaces dotted with vendors and bikes. We saw live chickens on sale for 8500 kwacha. When we passed through Zomba, Stephanie bought soursop from a fruit vendor through the open bus window. Looking back, the brief exchange over the moving glass felt strangely cinematic.

We did a lot of waving on those rides. As a bus full of Americans, we got stares wherever we went. The children always waved first. Their joy felt immediate and contagious. What struck me most was how young the country felt. Villages teemed with children, and the streets were full of fresh faces and strong, solid lines. It was a vivid contrast to my home city of Hong Kong, where the aging population looms heavy, and even to cities in the U.S. Here, the future felt right in front of us: beaming, barefoot, running beside our bus.

Double burdens

On our first day in Malawi, we visited the Kamuzu University of Health Sciences (KUHeS) campus, where we attended a series of lectures by professors in pressed black and blue suits. I squirmed in my oversized button-down and sneakers, feeling underdressed. Their lilting, British-infused accents reminded me of home. I kept thinking about how, in many ways, my world had been shaped by the same British institutional legacy, but the reality it had left behind in Malawi was different, harsher.

During the lectures, we learned that Malawi is experiencing the “double burden” of aging: infectious diseases and non-communicable diseases colliding in an unprepared healthcare system. Because of the lasting impact of HIV/AIDS, the country had not, until now, experienced generations that lived long enough to be called elderly. In the 1990s, during the height of the AIDS epidemic, life expectancy plummeted to around 40 years. In the decades that followed, life expectancy has climbed back into the 60s. It is a public health triumph, and yet, paradoxically, it brings forth a new crisis: the healthcare system, designed to fight outbreaks and acute illnesses, now finds itself battling chronic diseases that come with aging. Nearly a million elderly people live in Malawi today, 90% in rural areas, where resources are scarce and infrastructure is weak. Clinics are understaffed and understocked, and medical treatment is difficult to access.

Then there is the intersection of gender and aging. The lectures touched on the sinister ways in which older women, in particular, bear the brunt of cultural bias. They are often accused of witchcraft (which I didn’t think existed past the 17th century) and scapegoated for misfortunes that defy explanation. Even outside the realm of superstition, women suffer disproportionately. Many are financially dependent in the strict patriarchal society, yet paradoxically, they are the backbone of care. 62% of double orphans in Malawi are raised by their grandparents, most often grandmothers. These women hold together the frayed edges of a society still reeling from a crisis, yet they themselves are forgotten.

At the same time, the lectures also revealed how deeply traditional masculinity shapes health behaviors. One professor noted that in studies with AIDS patients, women are significantly more likely to recover, simply because they actually listen to doctors and seek treatment. Men, by contrast, often wait until symptoms are severe or ignore care altogether. In response, some clinics have even gone so far as to introduce a system of fast-tracking families who bring in the husband for check-ups, as a way to incentivize male participation. I still think about something Dr. Katundu said, half-joking: “The only place men go to seek care, especially mental health care, is the pub.” His joke was met with knowing laughter, but beneath it lies an uneasy truth. The constructed ideals of masculinity prevent men from seeking help and admitting vulnerability. In Malawi, as in so many places, gender dictates not just how people live, but how they suffer, and whether that suffering is ever seen.

In the eye of the storm

Soon after we arrived in Malawi, we had to cut our programming short because Tropical Cyclone Jude was fast approaching the city. Schools across the country had shut down until further notice, and the streets of Blantyre slowly emptied. For half a day, we listened to lectures over Zoom from our hotel. But even that didn’t last. Half the city lost power, including our hotel, which began running on its own generator. Lectures were interrupted by glitches and silence.

But the more I looked around, the more it felt like Malawi was suspended in the eye of a storm far larger than the one in the sky.

The Malawian economy was even more fragile than I first expected. 71% of the population lives below the poverty line, and 76% of the country still isn’t connected to the power grid, leaving most Malawians without reliable electricity. Tobacco remains the country’s primary export, accounting for 60% of foreign exchange earnings, even as global demand for it continues to decline. These numbers formed their own kind of storm.

On the day we left Blantyre for Liwonde, our schedule was almost thrown off again because major roads were blocked over protests over inflation, which had reached a staggering 34% in February. Each morning, I picked up the local paper from the hotel lobby, and every headline seemed to scream a quiet panic.

At the end of one of the lectures, a medical professor said he had one final slide to share: his vision for how Malawi could pull itself out of this crisis. I leaned forward, expecting something health-related. But when he clicked, what appeared on the screen was a screenshot of an article: “Mining Boom Looms.” Apparently, Malawi had recently discovered rare minerals that they are hoping to capitalize on in the next decade, though at the risk of more political turmoil. It was so jarring I almost laughed. After days of discussing medical research, understaffed clinics, and crumbling infrastructure, the foreseen solution was not to build up, but to dig down.

Tropical Cyclone Jude eventually passed. In the end, it didn’t impact our trip all that much. But I’m not sure Malawi’s own storm will pass so easily.

Visiting healthcare facilities

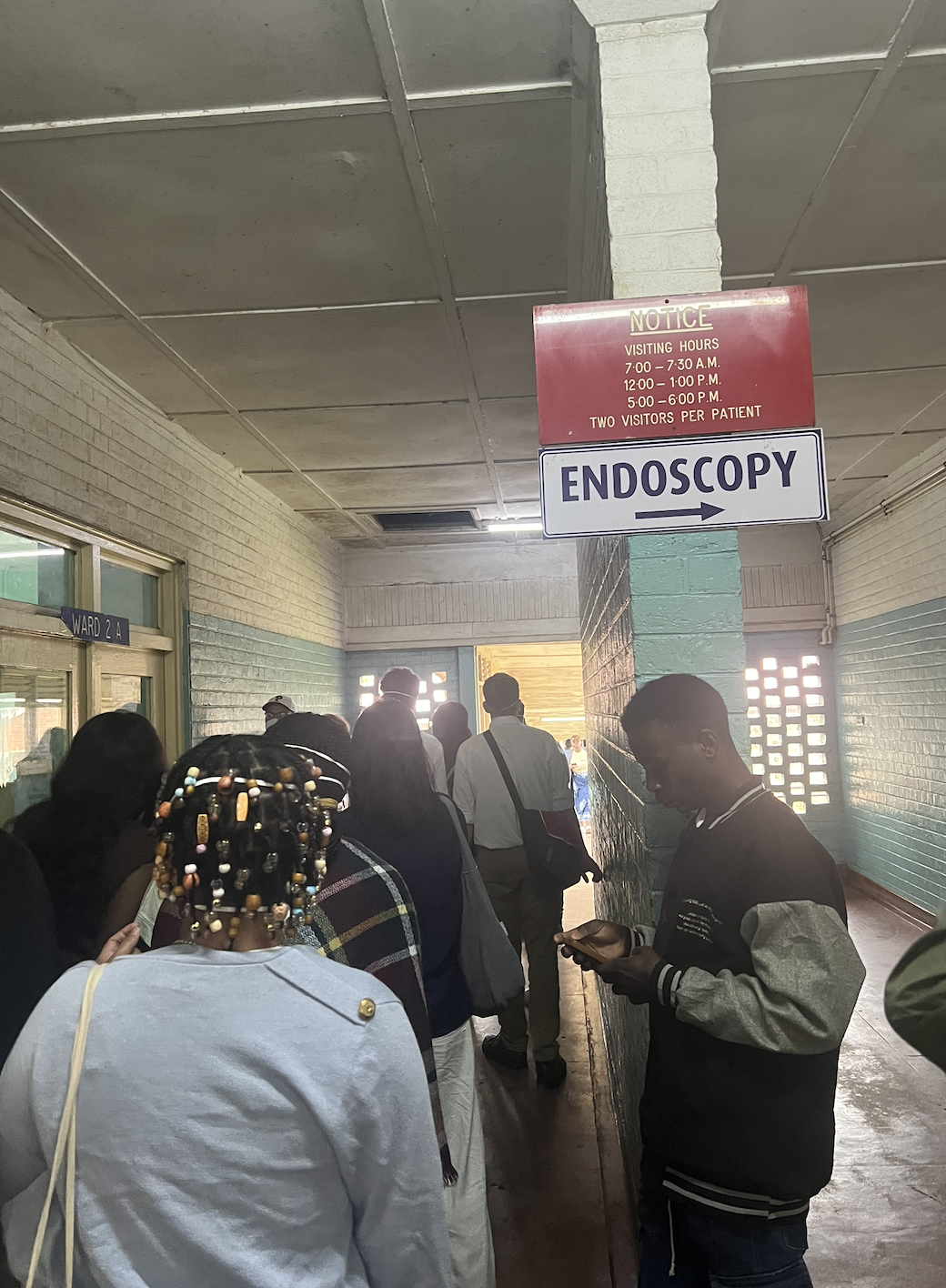

We toured Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, one of the biggest hospitals in the country, on our third day. This hospital challenged everything I thought I knew about what a hospital looked like. We visited the emergency ward, and it wasn’t the sterile, white-walled, fluorescent-lit image I had always pictured. Instead, it was dim and damp, the floors still slick from rain that had fallen earlier in the day. People lined the hallways, sat quietly on plastic chairs, or simply sprawled on the floor, waiting.

We met with a group of doctors who told us that a lack of funding, staff, and supplies defined every part of their day-to-day operations. In fact, there were only 60 medical staff in total in the entire hospital. During this visit, for the first time in my life, I wished I studied healthcare and had something more tangible to offer.

At a research facility we visited later that day, we learned that there are only 22 gynecologists in the entire country. There’s a national blood donation shortage, which means surgeries are delayed, childbirth becomes dangerous, and conditions that should be easily treatable turn fatal. One researcher said, almost with resignation, that most maternal deaths are preventable, but resources are scarce. In rural areas, many women give birth without any professional medical support at all.

At a third lab, I pointed to a sleek CD4/CD8 viral load testing machine and, out of curiosity, asked how much it cost. The researcher let out a dry laugh. “As expensive as a Lamborghini,” he said.

Safari in spring, sunset on Shire

At 5:30am on Thursday, we bundled into safari carts and headed to Liwonde National Park. I rode on top of the cart and kind of loved the bumpy ride, especially seeing the markets just beginning to stir awake, their stalls opening one flap at a time like yawning mouths.

The air was cool and thick with dew, and every breath smelled faintly of wet grass, woodsmoke, and something earthy I couldn’t quite name. It had rained earlier that week, and the scent of the soil felt alive. Because it’s the wet season, the landscape was lush and overgrown – a leafy tangle brushing the sides of our cart rather than the dusty, golden plains you usually imagine. I worried we wouldn’t see many animals, but we spotted kudus, gazelles, monkeys, and more.

About an hour in, we saw our first elephant. It stopped on the side of the road and started feeding: curling its wrinkly trunk inward to gather a bundle of leaves and slowly bringing it up to its mouth. You could hear the soft crunch of leaves as it chewed. We held our breath. I didn’t expect the elephant to be so silent. You think something that massive would crash into the scene with drama, but it moved with the calm assurance of something that had been here long before us. As we continued driving, we saw an entire pack of elephants in a clearing. I was mesmerized by their ears, which reminded me of large mushrooms, flapping collectively in slow motion.

Later that afternoon, we boarded a boat to cruise along the Shire River in search of hippos. This region has about 2,000 of them, and their numbers are growing. Hippos live in a strange summer limbo: their skin is so sensitive they can’t spend long in direct sunlight, but they also can’t breathe or sleep underwater. So during the day, they stay submerged, surfacing only briefly for air.

Spotting them felt like a visual game of whack-a-mole. The second someone would point –”Over there! Look!” – at a pair of tiny ears bobbing above the water, they’d vanish again. Then, somewhere else, another pair would appear. Surface, sink. The river was like a living thing, constantly rearranging itself. It was funny and frustrating, like chasing shadows.

Towards the end of the cruise, just as the golden light began to drape the river in honey, a single hippo burst from the water. It revealing its full, majestic torso, shaking off droplets like crystals in the evening light. There was this audible gasp from everyone on the boat. The sheer presence of it was staggering. Just as quickly, it was gone again, as if it had only popped up to remind us it was real.

We also spotted crocodiles sunning themselves lazily on the banks. At one point, I noticed a small white bird hopping around one of them. It danced so close to the crocodile’s gaping jaws that I instinctively winced, convinced it was about to be eaten. But it didn’t. The crocodile stayed perfectly still. Later, our guide explained that this is a well-known example of symbiosis. The unlikely balance spoke to the delicate wisdom of coexisting, even when instinct might suggest otherwise. I found it oddly moving.

The warm heart of Africa

The first word our tour guide Ted teaches us in chichewa is zikomo, which means thank you.

“We say it a lot here,” he tells us, and over the course of the trip, I come to understand why. Malawi is known as the “warm heart of Africa”, and this culture of warmth lingers in handshakes, in sunny smiles, in the way people look each other in the eyes when they speak.

But I wonder what zikomo means in moments when there is nothing left to give.

On our last day, we visit the Njobvu Cultural Village. As we step off the bus, we are met with a welcome so warm it nearly overwhelms me. We are handed slices of a yellow melon, which tastes like a cross between a pear and a potato. It is unfamiliar yet comforting, like so much of this trip.

We try our hands at palm leaf weaving and traditional flour pounding, tasks that appear effortless in the hands of those who have done them for a lifetime. But our weak arms tire quickly, and we laugh as the villagers take pity on us and finish what we start. We sit for a Q&A session with the village chief while he weaves a bedmat. The chief tells us that he is chosen not by a predetermined lineage, but by the women in his family, who vote to decide who among them is best suited to lead. This surprises us all, given the many patriarchal structures we’ve encountered so far. I look around at the women of the village, and I wonder how different the world would look if more societies were built on her wisdom.

We visit a traditional healer, who shows us his collection of roots, powders, and herbs. He has remedies for everything from yellow fever to pregnancy to what he calls “natural Viagra.” One powder is meant for “barren women.” In the healer’s small, dark hut, I think about the weight of expectation placed on women’s bodies and the burdens they carry. In another home, we learn about the red and white beads that women hang in the bedroom, a signal to their husbands about whether or not they are on their period. Here, sex is spoken of in colors, in small gestures, but mostly in silences.

At the end of our visit, we are gathered in a circle and our guide grins mischievously: “It’s Friday, so we dance!” The villagers take our hands, spinning us, pulling us into their celebration. At first, our group was hesitant and self-conscious, but as the drums begin to pulse, we couldn’t help but move. I notice an old woman dances with a fire in her step that defies time. I admire her all the more after learning about the witchcraft accusations that often target elderly women. Here, in this moment, she is nothing but light.

But what strikes me most about the village is the children.

They follow us everywhere, surrounding us in a circle, staring at us with wide, inquisitive eyes. They rush to hold our hands, latching onto our arms. At any given moment, each of us has three or four children holding onto us. I have never felt so instantly, unconditionally embraced.

“What’s your name?” they ask over and over. “So-phi-a,” I say, “What’s yours?” I try to continue the conversation, asking how old they are, where they like to play. But they just stare up at me, my words falter in the space between us. So we stick to names. And smiles. And swinging our hands. And sometimes, that’s all you need.

But the children don’t only reach for us in curiosity. They also reach for us in need.

As we drive through the village, children chase the bus, their voices rising in a chorus of high-pitched cries: “Money, money, money, money!”

At first we couldn’t believe that that’s what they were saying. They laugh and yell like it’s a game, their feet kicking up dust as they run alongside us. I don’t know if they fully understand what they’re asking for, or if it is a phrase they’ve been taught to say. Which would be more unsettling: if they do know what it means, or if they don’t?

Our professor had given us clear instructions before arrival: do not give anything – no food, no gifts, no money. The village is part of a fieldwork site, and it would disrupt the research. Back then, we all agreed easily, nodding along. But at the village, when the kids are swinging from your clothes and start to make asks, we all falter.

“Give me my bottle,” one girl says, pointing at the plastic water bottle in my hand.

“Give me my bangle,” another girl whispers, lightly touching the black hair tie on my wrist. She tugs at my sleeve and looks up, her eyes bright and still and open, like a door held open, and I want to run through it.

When we leave, the children gather beside the bus, waving, laughing. Their joy is still there, irrepressible. But I can’t help but wonder what the world will ask of them in the years to come, and whether they will still have hands to hold onto when they need them most.

Goodbye, Malawi

During the trip, some of the tragedy we witnessed felt softened by the lens of curiosity. I moved through the hospitals and villages with eyes wide open, absorbing details with a fascination protected by the distance that being a visitor brings.

I also have to acknowledge that our trip was deeply insulated. Penn had taken every measure to ensure our safety: vaccinations and pills, strict curfews, clean bottled water, a private charter bus. We stayed in one of the country’s most luxurious hotels in a room bigger than my own in Philadelphia. We had buffet breakfasts each morning. We barely walked outside. We moved from site to site in our own air-conditioned bubble. We saw so much, yet still so little, and it would be disingenuous to pretend otherwise.

At our debrief, Professor Kohler closed with a reflection of her own. She said what she admired most about Malawi was the resilience of the people we met. The way they carried on, adapted, and endured with quiet determination. “I hope,” she said, “that we can all take a tiny piece of the warm heart of Africa with us.”

What does it mean to carry a piece of a place with you? I’ve thought about that a lot since coming home. I’ve done it all: souvenirs, photos, journal entries. But none of that feels like enough.

Malawi was never ours to fully know, especially not in ten days. We glimpsed so much, and yet touched so little. But I’d like to think that it gave us a reframing of what we consider urgent, or fair, or broken, in the world. And a heart that’s just a little bit warmer than before.

Read Related Blogs

What the Wind Knows: Notes from the Steppe

PGS: Mongolian Civilization: Nomadic and Sedentary Will, one of the Penn Global Seminar Correspondents, shares his experience abroad during the May 2025 travel period. Follow along with the group of correspondents on our blog and…

A Thank You Letter to Penn and the World

PGS: Disability Rights and Oppression: Experiences within Global Deaf Communities Tasmiah, one of the Penn Global Seminar Correspondents, shares her experience abroad during the May 2025 travel period. Follow along with…

In the Absence of Certainty

PGS: Rivalry, Competition and International Security in Northeast Asia Lala, one of the Penn Global Seminar Correspondents, shares her experience abroad during the May 2025 travel period. Follow along with the…